Review by Zoe Blunt | Originally published in the March/April 2012 issue of Canadian Dimension magazine. Subscribe here.

I first heard about Deep Green Resistance in the middle of a grassroots fight to stop a huge vacation-home subdivision at a wilderness park on Vancouver Island. Back then, it hadn’t really occurred to me that a book on environmental strategy was needed. Now I can tell you, it’s urgent.

I first heard about Deep Green Resistance in the middle of a grassroots fight to stop a huge vacation-home subdivision at a wilderness park on Vancouver Island. Back then, it hadn’t really occurred to me that a book on environmental strategy was needed. Now I can tell you, it’s urgent.

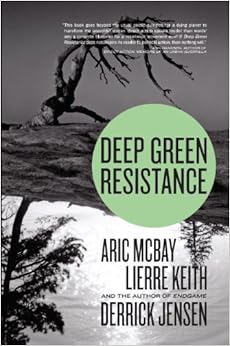

Deep Green Resistance (DGR) made me a better strategist. If you’re an activist, then this book is for you. But be warned: at 520 pages (plus endnotes), it’s not light reading. Quite the opposite — DGR dares environmental groups to focus on decisive tactics rather than mindless lobbying and silly stunts.

“This book is about fighting back. And this book is about winning,” author Derrick Jensen declares in the preface to this three-way collaboration with Lierre Keith and Aric McBay.

Keith, author of The Vegetarian Myth, opens the discussion with an analysis of why “traditional” environmental action is self-defeating. For those who’ve read Jensen’s Endgame, or who have experienced the frustration of born-to-lose activism, Keith’s analysis hits the nerve.

The DGR philosophy was born from failure. In a recent interview, Jensen recounts a 2007 conversation with fellow activists who asked, “Why is it that we’re doing so much activism, and the world is being killed at an increasing rate?” “This suggests our work is a failure,” Jensen concludes. “The only measure of success is the health of the planet.”

If we keep to this course, as Keith points out, the outcome is extinction: the death of species, of people, and the planet itself. Environmental “solutions” are by now predictable, and totally out of scale with the threat we’re facing. Cloth bags, eco-branded travel mugs, hemp shirts, and recycled flip-flops won’t change the world. Wishful thinking aside, they can’t, because they don’t challenge the industrial machine. It just keeps grinding out tons of waste for every human on the earth, whether they are vegan hempsters who eat local or not. So these “solutions” amount to fiddling while the world burns.

Aric McBay, organic farmer and co-author of What We Leave Behind, says Deep Green Resistance “is about making the environmental movement effective.”

“Up to this point, you know, environmental movements have relied mostly on things like petitions, lobbying, and letter-writing,” McBay says. “That hasn’t worked. That hasn’t stopped the destruction of the planet, that hasn’t stopped the destruction of our future. So the point is if we want to be effective, we have to look at what other social movements, what other resistance movements have done in the past.”

Keith notes that a given tactic can be reformist or radical, depending on how it’s used. For example, we don’t often think of legal strategies as radical, but if it’s a mass campaign with an “or else” component that empowers people and brings a decisive outcome, then it creates fundamental change.

“Don’t be afraid to be radical,” Keith advises in a recent interview. “It’s emotional, yes; this is difficult for people, but we are going to have to name these power structures and fight them. The first step is naming them, then we’ve got to figure out what their weak points are, and then organize where they are weak and we are strong.”

Powerful words. But by then I was desperate for a blueprint, a guidebook, some signposts to help break the deadlock in our campaign to save the park. Two hundred pages into DGR, we get down to brass tacks, and find out what strategic resistance looks like.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t a guerrilla uprising.

To be clear, Deep Green Resistance is an aboveground, nonviolent movement, but with a twist: it calls for the creation of an underground, militant movement. The gift of this book is the revelation that strategies used by successful insurgencies can be used just as successfully by nonviolent campaigns.

McBay argues convincingly that it’s the combination of peaceful and militant action that wins. He emphasizes that people must choose between aboveground tactics and underground tactics, because trying to do both at once will get you caught.

“The cases of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X exemplify how a strong militant faction can enhance the effectiveness of less militant tactics,” McBay writes. “Some presume that Malcolm X’s ‘anger’ was ineffective compared to King’s more ‘reasonable’ and conciliatory position. That couldn’t be further from the truth. It was Malxolm X who made King’s demands seem eminently reasonable, by pushing the boundaries of what the status quo would consider extreme.”

What McBay calls “decisive ecological warfare” starts with guerrilla movements and the Art of War. Guerrilla fighting is all about asymmetric warfare. One side is well-armed, well-funded, and highly disciplined, and the other side is a much smaller group of irregulars. And yet sometimes the underdog wins. It’s not by accident, and it’s not because they are all nonviolent and pure of heart, but because they use their strengths effectively. They hit where it counts. The rebels win the hearts and minds and, crucially, the hands-on support of the civilian populace. That’s what turns the tide.

McBay notes, for example, that land reclamation has proven to be a decisive strategy. He argues that “aboveground organizers [should] learn from groups like the Landless Workers’ Movement in Latin America.” This ongoing movement “has been highly successful at reclaiming ‘underutilized’ land, and political and legal frameworks in Brazil enable their strategy,” McBay adds.

Imagine two million people occupying the Tar Sands. Imagine blocking or disrupting crucial supply lines. Imagine profits nose-diving, investors bailing out, brokers panic-selling, and the whole top-heavy edifice crashing to a halt.

The Landless Workers’ Movement operates openly. Another group, the Underground Railroad, was completely secret. Members risked their lives to help slaves escape to Canada. A similar network could help future resisters flee state persecution. Those underground networks need to form now, McBay says, before the aboveground resistance gets serious, and before the inevitable crackdown comes.

DGR categorizes effective actions as either shaping, sustaining, or decisive. If a given tactic doesn’t fit one of those categories, it is not effective, McBay says. He emphasizes, however, that all good strategies must be adaptable.

To paraphrase a few nuggets of wisdom:

Stay mobile.

Get there first with the most.

Select targets carefully.

Strike and get away.

Use multiple attacks.

Don’t get pinned down.

Keep plans simple.

Seize opportunities.

Play your strengths to their weakness.

Set reachable goals.

Follow through.

Protect each other.

And never give up.

Guerrilla warfare is not a metaphor for what’s happening to the planet. The forests, the oceans, and the rivers are victims of bloody battles that start fresh every day. Here in North America, it’s low-intensity conflict. Tactics to keep the populace in line are usually limited to threats, intimidation, arrests, and so on.

But the “war in the woods” gets real here, too. I’ve been shot at by loggers. In 1999, they burned our forest camp to the ground and put three people in the hospital. In 2008, two dozen of us faced a hundred coked-up construction workers bent on beating our asses.

Elsewhere, it’s a shooting war. Canadian mining companies kill people as well as ecosystems. We are responsible for stopping them. We know what’s happening. Failing to take effective action is criminal collusion.

Wherever we are, whatever we do, they’re murdering us. They’re poisoning us. Enbridge, Deepwater Horizon, Exxon, Shell, Suncor and all their corporate buddies are poisoning the air, the water, and the land. We know it and they know it. Animals are dying and disappearing. There will be no end to the destruction as long as there is profit in it.

This work is scary as hell. That’s why we need to be really brave, really smart and really strategic.

We have strengths our opponents will never match. We’re smarter and more flexible than they are, and we’re compelled by an overwhelming motivation: to save the planet. We’re fighting for our survival and the survival of everyone we love. They just want more money, and the only power they know is force.

As Jensen says, ask a ten-year-old what we should do to stop environmental disasters that are caused in large part by the use of fossil fuels, and you’ll get a straightforward answer: stop using fossil fuels. But what if the companies don’t want to stop? Then make them stop.

Ask a North American climate-justice campaigner, and you’re likely to hear about media stunts, Facebook apps, or people stripping and smearing each other with molasses. Not to diss hard-working activists, but unless they are building strength and unity on the ground, these tactics won’t work. They’re not decisive. They’re just silly.

Of course, if the media stunts are the lead-in to mass, no-compromise, nonviolent action to shut down polluters, I’ll see you there. I’ll even do a striptease to celebrate.

© 2012 Zoe Blunt

Derrick Jensen on coming to grips with this destructive culture

Derrick Jensen on coming to grips with this destructive culture