Originally published in The Dominion, August 2009

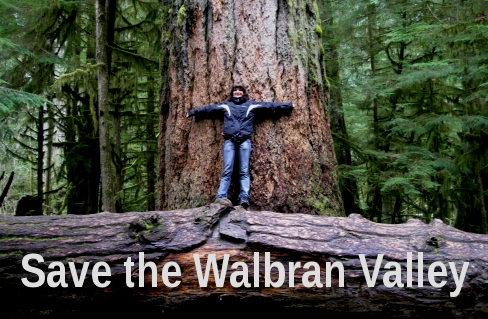

Once upon a time, about 800 years ago, a seed sprouted beside a river in a forest. As the years and the centuries passed, the tiny seedling grew to be the largest Spruce in the country, a jagged gnarly moss-covered monster that blocks out the sun. It’s covered with burls and shelf fungi the size of ponies. Ferns and berry bushes sprout from its upper branches. Great horned owls perch on its crag in the middle of the night and coo like doves, and wood ducks nest in a hollow in the trunk, thirty feet from the ground.

One day not long ago, a handful of free-spirited young people escaped the decaying city and roamed up the coast, leaving the highway and wandering for hours until they came to the Spruce. They were awestruck by the mountain-sized tree and by the massive broken limbs laying about on the ground. A sign near the Spruce warned people not to camp underneath its canopy, because falling limbs could crush a person like an ant.

The travellers said: “Near this giant Spruce (but not too near) is where we’ll camp, and we’ll invite all our friends and all the free-spirited people we know to share stories and learn from each other and play music and have a feast.”

And that’s what they did. This is their story.

A late spring storm tossed the branches of the Spruce and pelted the young people with rain and spruce needles as they hoisted up tarps and built a kitchen. They worked out how to boil and filter the river water to make it safe for drinking, and placed hand wash stations at the kitchen and the latrines so everyone would stay healthy. They dragged dead fallen trees from the forest and split and chopped firewood and made shelves to keep things off the ground. The rain stopped, the birds sang and the river splashed along, and the Spruce shaded them from the sun as they worked.

Soon enough, more wild folks came from the decaying cities, and the places around and between the cities, and even from other countries. They came in ones and twos and threes and by the dozen, and each, in turn, stood awestruck in the shade of the giant Spruce, and goggled at the thousands of tadpoles that turned the shallow river edges black as ink and the nodding thickets of sweet, fat salmonberries everywhere. They laughed out loud in delight and agreed they had never seen such a beautiful place.

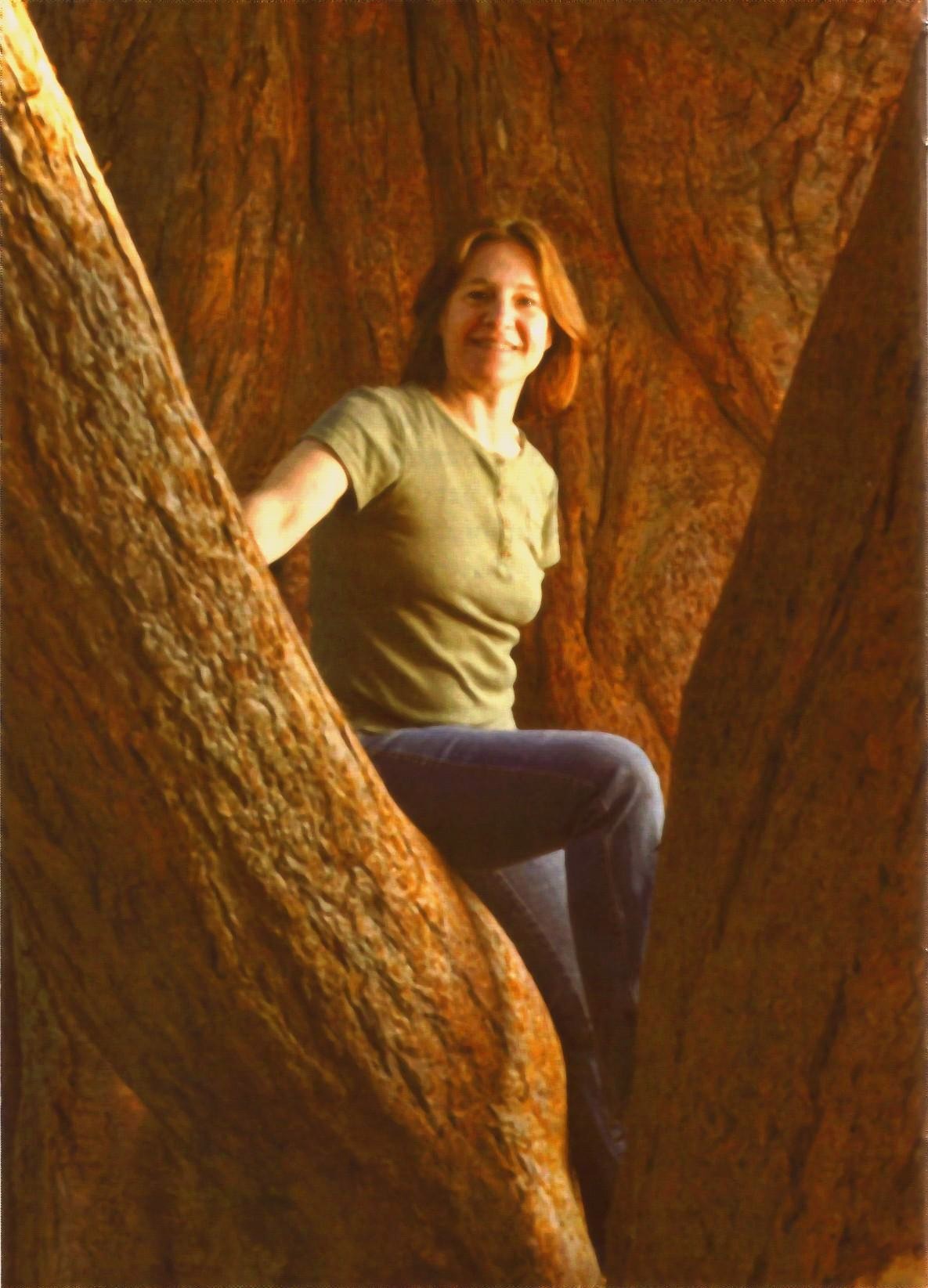

The young ones were joined by elders and middle-aged people who were also pretty wild, and everyone was in such high spirits that they sang and cheered long into the night. The next morning, a dozen people surrounded the Spruce and festooned it with ropes. They gently fastened huge webbing straps around a secondary trunk, being careful not to dislodge giant fungi and the mats of moss like haystacks that could swallow up a person. The older climbers showed newcomers how to use the ropes and harnesses to safely climb up the tree and stand on the limbs among the ferns, high up in the canopy. Laughter rang out through the clearing as the new climbers swung from the ropes and waved at the startled birds above and their friends far below.

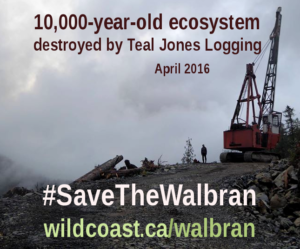

Later, people gathered in a circle in the clearing. They sat cross-legged on the ground and discussed what it means to be an eco-warrior. They made a list of their heroes – people who risked their freedom and their safety for a higher cause. They shared stories about how these heroes inspired them, and why the system calls them criminals and terrorists. They considered the harsh penalties that are sometimes handed down to eco-warriors, and the intense pressure that’s put on them to abandon their principles.

They discussed what it means to be free-spirited wild humans. They compared notes about the coming collapse of civilization and decided it would be the best thing that could happen for almost everything alive on the planet. They shared their experiences with police and authorities and showed off their scars. They learned about non-violent civil disobedience and played a game to practice defending the Spruce against chainsaws.

It was loud and raucous, and it was quiet and thoughtful, and through it all the birds sang and trilled and the river splashed along and the Spruce cast its cool shade across the camp.

That night, some of the wild boys and girls got drunk on homemade hooch and spent the whole night singing and screaming “Fuck the police” and howling like animals. The owls hooted back at them indignantly. “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?” .

The next afternoon, the Forest Service Ranger and the Forest Service Supervisor came bouncing down the road in a Jeep. An anonymous tip had told them there was a rave party at the Spruce and they should shut it down. But after a few minutes, they realized there was no rave, just happy campers. They were so charmed by the scene that they smiled and waved and turned around and drove back to the Fairy Lake ranger station.

The wild people spent six days and nights talking and learning, sharing ideas about diversity of tactics and jail solidarity and security culture and how to identify edible plants. They played Capture the Flag and sprawled on the riverbank in the sun and let the tadpoles tickle their toes. They ate the sweet salmonberries until every bush within reach was picked clean. They wrestled and chased each other around and climbed up and down the Spruce like a band of monkeys.

When the sun went down, they lit candles and laid cedar logs on the fire, and the tarps and tents glowed in the light of the dancing flames. Two great horned owls circled the camp and landed in the crag of the Spruce and cooed like doves while the Moon shone through the great mossy branches. And the people around the fire sang their favourite songs and laughed and pledged to defend the land, to guard the owls and tadpoles and wood ducks, and to protect each other from harm, no matter what.

The Spruce stood over the wild humans as they laughed and talked and sang. and a shiver passed through its branches, like the wind from a coming storm.

Far away, beyond human hearing, the city sputtered and crackled with cars, electricity and consumption. But here in the darkness, the Spruce stood trembling and listening, and it heard in the people’s voices the life force that reclaims everything, the irresistible power of nature that overgrows roads and collapses buildings, crumbles concrete and asphalt and cars, and drives tiny seeds to sprout on rocky riverbanks and grow for 800 years until they block out the sun. The ancient Spruce felt the life spirit — stronger and older than any civilization — as waves of laughter rippled out from the tiny, fragile humans below. The Spruce saw the wild earth spirit in them and in every living thing. And it was good.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

Derrick Jensen on coming to grips with this destructive culture

Derrick Jensen on coming to grips with this destructive culture