The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

Activism is a path to healing from trauma. It’s taking back our power to protect ourselves and our future.

From a spoken-word presentation in Victoria BC, 2009

Thank you for the opportunity to launch my speaking career. Some of you may know me as a writer and an advocate for social and environmental justice. Others may know me as a cat-sitter, odd-jobber, and temp slave. (Laughter)

I knew when I started out as an activist that I would never be a millionaire and I was right. But I have a certain freedom and flexibility that your average millionaire might envy.

The market demand for social justice advocates is huge right now. It’s a growth industry. And the job security is fantastic – there is no shortage of urgent issues demanding our attention. Experience is not necessary, people come to activism at every age and stage in their lives. It’s that easy!

OK, it’s not actually that easy. (Laughter) But it is a fascinating time to be a “radical.”

There is a great tradition of courage and action here on Vancouver Island. There is potential for even greater future action, so we are doing everything we can to nurture that potential. Building community, linking up networks, teaching, learning, coming together, healing – this is all part of the movement.

For most of my adult life, I suffered from social phobia. I was afraid of authority, filled with self-doubt, paralyzed by anxiety. Getting interviewed live on national TV doesn’t make that go away. But hiding under the covers doesn’t cure it either. So my insecurities and I just have to get out there and do our best.

What compels me is the knowledge that we’re rewriting the script – the one that says, “You don’t make a difference. It is what it is, you can’t fight city hall, the big guys always win.” We can remember that we are not powerless. And when we choose to stand up, it is a huge adrenaline rush – bigger than national TV or swinging from a tree top. That’s the reward – that flood of excitement that comes from taking back our power and using it effectively, for the collective good.

It helps to get love letters from friends and strangers who want to thank me for standing up for what’s important, and who get inspired to take action themselves.

But it’s not all warm fuzzies and celebratory toasts. We face backlash and punishment and threats to our lives and safety.

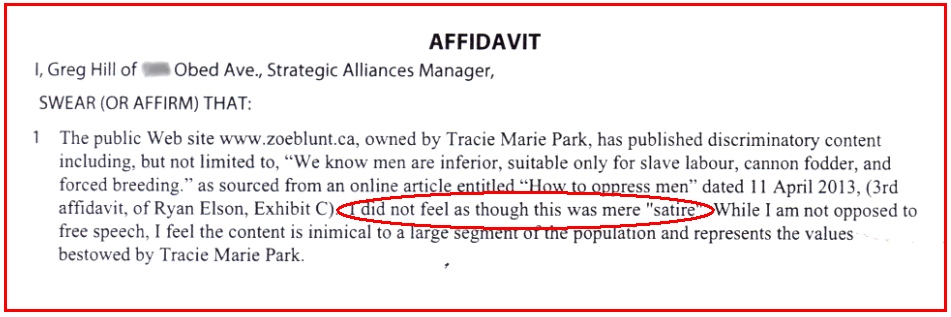

I led a workshop for new activists this year, and I asked them, “Who are your heroes?”

They named a dozen. Gandhi. Martin Luther King. Tommy Douglas. Rosa Parks. These folks led amazing, heroic movements, but our discussion focused on the ferocious backlash they faced. British media reports on Gandhi when he was challenging the monarchy had the same tone as white Southerners responding to Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the bus. It was vicious. “Uppity and no-good” were some of the polite terms. They were targeted with hate speech and death threats. We hear the same now about whistleblowers. And feminists and environmentalists. It can be terrifying.

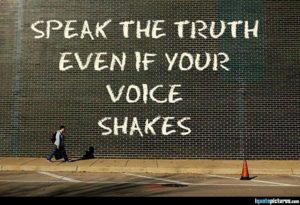

The more we challenge the status quo, the more the entrenched powers attack us. The more effective we are, the more they attack us. As Gandhi said: “First they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, then you win.”

The fight for justice and liberation won’t be won by popularity contests.

Every “hero” finds her own way of dealing with the counter-attacks. Some laugh it off. Some pray, some cry on their friends shoulders. Some go on the counter-offensive, some compose songs, some write long academic papers deconstructing their opponents’ logic. The important thing is, they deal with it, and they don’t give up.

We take care of each other as a community. Because we are all so fragile. Because there is so much trauma and despair everywhere and it affects everyone. But inside that despair, in all of us, there is a solid core of love for the earth and the knowledge that we can act in self-defense. That’s where we find strength.

It’s humbling to note that the economic downturn has done more to preserve habitat and stop climate change than all of our conservation efforts of the past years combined. We take responsibility for recycling and turning down the thermostat, but who is responsible for the scale of destruction from the Tar Sands? That project is the equivalent of burning all of Vancouver Island to the ground. It negates everything we could hope to do as individuals to fight climate change.

How do we deal with that horrible reality? I couldn’t, for the first year of the campaign. I didn’t want to look at the pictures and hear the news stories about the water and air pollution and the rates of illness among the Lubicon Cree people. The scale and the horror of it were too great.

I’ve worked on toxics campaigns and I dread them. Old-growth campaigns are inspiring, because where the action is, the forest is still standing – it’s beautiful and magical and we’re defending nature’s cathedral from the bulldozers and chainsaws. The good earth is here, and the evil destructive forces are over there. It’s clearcut, so to speak. But when a toxics campaign is underway, the damage has been done. The landscape is poisoned and people have cancer and spontaneous abortions, and the birds, the fish, the animals, are dead and dying. It is a scene of despair.

If it sounds traumatizing, it is. And we are all traumatized.

Look at this landscape – concrete, pavement, bricks and mortar, toxic chemicals, but underneath, the earth is still there. We have whole ecosystems slashed and burned without so much as a by-your-leave. We’ve lost whole communities of spruce, marmots, murrelets, arbutus, sea otters, and geoducks. These are terrible losses.

And we humans suffer on every level. Is there anyone here who doesn’t know someone who’s had cancer? Who hasn’t seen the damage caused by diseases of civilization? Who here hasn’t been forced to do without for lack of money? Are there any women here who have never been sexually harassed or raped or assaulted?

(Silence)

Something fundamental has been taken from us here. How do we deal with these losses?

I consider myself fortunate because after a lifetime of abuse from my family and male partners, I participated in six months of Trauma Recovery and Empowerment at the Battered Women’s Support Centre in Vancouver.

And I got to know the stages of trauma recovery:

Acknowledge the loss, understand the loss, grieve the loss.

And the stages of grief:

Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

These steps are a natural and necessary response to the loss of a loved one, and also to the loss of our humanity and the places we love.

There are people living in national sacrifice zones, people who burn with determination to make change. They are angry, and they have a right to be. I am angry because I’m not dead inside, in spite of all they’ve done to me. Anger is part of the process of grief, and it’s useful. It grabs us by the heart when people are hurting the ones we love.

For me, part of the process is taking action – rejecting helplessness and taking back power. Stopping the bleeding and comforting the wounded.

I fall in love with places and I want to protect them. I fell in love with the Elaho Valley and some of the world’s biggest Douglas Firs in 1997. That forest campaign was a pitched battle, far from the urban centers, against one of the biggest logging companies on the coast at that time.

In the third year of the campaign, I walked into my favourite campsite shaded by majestic cedars. I saw the flagging tape and the clearcut boundaries laid out, and I realized it was all doomed. I could see the end result in my mind’s eye: stumps and slash piles as far as the eye could see, muddy wrecked creeks, a smoldering ruin.

I realized no one was going to come and save this place – not Greenpeace or the Sierra Club, no MP’s private member’s bill, or whatever petition or rally was being planned back in the city. It was as good as gone. All we had to do was stand aside and do nothing, and this incredible, irreplaceable forest would be just a sad memory.

But after that realization, and after the despair that followed, I had a profound sense of liberation. If it is all doomed, then anything we do to resist is positive, right? Anything that stops the logging, even for a minute, or slows it down, or costs the company money, or exposes it to public embarrassment and hurts its market share, is positive – it keeps the future alive for that one more minute, one more hour, one more day. It was a revelation.

Acceptance, for me, meant being able to act to defend the place I loved. It meant standing up to the bullies and refusing to let them take anything more from me.

In the third year of the Elaho campaign, it was just a handful of people rebuilding the blockades, defying the court orders and continuing the resistance. We didn’t quit when the police came, or when we were called “terrorists” and “enemies of BC.” We didn’t quit even after 100 loggers came and burned our camp to the ground and put three people in the hospital.

The attack was a horror show. People were in shock. But a crew was back with a new camp five days later. By then, the raid was national news. And our enemies had nothing left to throw at us. The loggers didn’t know what to do next. Short of killing us, what more could they do?

We had called their bluff.

We didn’t know about the negotiations going on behind the scenes. We didn’t realize that we had already cost the loggers more than they could hope to recoup by logging the entire rest of the valley. (They were operating on very slim profit margins.) We found out when the announcement came that the logging would stop. And it never started again. We won. Now the Elaho Valley is protected by the Squamish Nation — and by provincial legislation — as a Wild Spirit Place.

The violence of the mob showed the level of fear and desperation of the losing side. It was their weapon of last resort and it didn’t work. And they lost.

In the fourth year of the stand for SPAET – the campaign to stop the development and protect the caves, the garry oaks, and the wetlands on Skirt Mountain. We faced the same tactics – we were called “terrorists,” and in 2007, the developers sent 100 goons to rough up people at a small rally. And again, most of our comrades are in shock. There’s only handful of us still bashing away at the next phase of development.

But we are winning. The other side has thrown everything they have at us and they have nothing left.

There are still sacred sites on SPAET. The cave is still there, buried under concrete.

Meanwhile, the developer is bankrupt. His little empire fell apart, either because of our boycott campaign, bad karma, or because it was operating on the slimmest shadiest margin. We took the next phase of development to court. Our campaign, and the economic downturn, turned out to be enough to scare off investors and cancel the project, at least for now.

This work is difficult, painful, and traumatic. So the first step to courage is to acknowledge that pain and loss. We need to name what has been taken from us. Then we can cry, and rage, and grieve. We can name the ones who are doing the damage. We can reach down inside and find our core strength and our truth, and use it. That’s where courage comes from.

Martin Luther King said, “Justice shall roll down like waters, righteousness like a mighty stream.” But I’m impatient. I want to see that mighty stream now – what’s the hold-up? What’s holding us back, when there’s so much to do?

We’re not heroes, actually – none of us is smart enough, or tough enough, or connected enough, to take this on alone. We don’t have superpowers. We are only human, we struggle and suffer and sometimes, we win.

Some folks assume I have some unique privilege or special power that gives me an edge. Nope. I have material analysis and long-range vision, but mostly I’m flailing around on the political landscape, taking potshots when I see an opening. Sometimes it’s intuition, and it pays off. When we are right, it is amazing. When we win, it sets a precedent for the future.

In order for evil to prevail, all that’s required is for good people to do nothing. Don’t be one of those good people.

Activism is part of the healing. It’s taking back our power to protect ourselves and our future.

Thank you for the opportunity to tell these stories today.

(Applause)

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.