The thirty-year-old activist (and comrade of mine) was convicted of obstructing justice in December 2006. A BC Supreme Court judge refused to believe police endangered his life in a tree-sit one hundred and fifty feet off the ground. He is facing nine months in jail at his sentencing in February 2007.

“Even had someone died six years ago, it seems the courts would have found that it was our own fault.”

The Douglas firs in the upper Elaho Valley are some of the biggest in Canada. Photo: Western Canada Wilderness Committee.

As the battle raged six years ago, it looked like the old-growth forests of the Elaho Valley were doomed. Eighty percent of the area had already been logged. A priceless grove of record-setting trees was about to fall. Wilderness advocates from the coast and across the province pledged to help defend the area. Hundreds visited and fell in love with the canyonlands along the Elaho River in British Columbia’s Coast Mountains near Whistler.

But International Forest Products (Interfor) kept marching on. Each year, chainsaws and bulldozers chewed through whole mountainsides full of cedar, fir and hemlock, leaving massive scars on the steep slopes and filling fish streams with silt.

Repeated appeals to the government and Interfor failed, so forest advocates took to civil disobedience and peaceful protests to stop the logging. I was with Zarelli and other forest defenders on the frontlines of Interfor’s logging operations for months at a stretch. We built a protest camp at the end of the road from downed trees and tarps, and took turns cooking communal meals, hauling water, and playing cat-and-mouse games with the loggers. By the end of July, two dozen people were camped at the road’s end.

We were holding the line to protect thousand-year-old firs and cedars north of Lava Creek. The previous year, contractors had punched in a logging road over fierce resistance and incredibly rough terrain. The battle front shifted to the new bridge over Lava Creek, which was the only way to access the upper valley.

The blockade on Lava Creek Bridge, July 2000. Photo: Zoe Blunt.

Using peaceful civil disobedience in this case meant putting our bodies on the line in such a way that the workers would have to risk killing someone to carry on with the logging. Normally, it’s an effective method for stopping traffic. But years of confrontations in the Elaho Valley taught us that blocking the road on the ground invited certain disaster. Loggers for Interfor had a deep and abiding hatred of tree-huggers, and they expressed it with death threats and violent attacks on protestors whenever they could.

In September 1999, a hundred loggers descended on the camp to make good on their threats to get rid of us once and for all. I was in Whistler that day, and others were in court. The eight remaining campers tried reasoning with the mob, but to no avail. Loggers beat and choked three people, who were teken to hospital after the attack. They burned the camp to the ground, destroying $30,000 worth of equipment, gear and personal belongings. Police took six hours to respond to 911 calls, and once they arrived, they arrested the tree-sitter and let the thugs go.

Peaceful civil disobedience is a real challenge in these circumstances.

But the violence by loggers – and what was seen as complicity by police – only made the protestors more determined to use peaceful means to stop the destruction.

“Everything we were doing kept getting more escalated,” Zarelli says. “We didn’t want to block the road for just a day or two.” He and three friends set out to create a hard blockade that would keep the road blocked for a couple weeks. They devised a system to block the bridge, put themselves in harm’s way, and stay out of reach of the police, all at the same time.

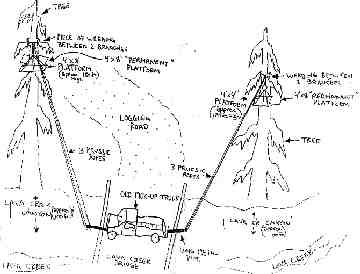

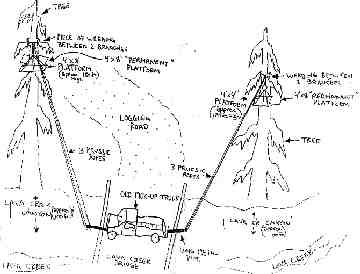

Lava Creek Bridge is wood, concrete and steel, 120 feet long and 12 feet wide, spanning a rugged canyon. A hundred feet below, the creek roars and foams. At the north end, high up in a pair of gigantic firs, Zarelli and three others perched on small platforms attached by ropes and conduits to a barricade on the bridge twelve stories below.

Two platforms, 150 feet up in the tree at left, are difficult to see from the ground. A yellow gear bag hanging below the canopy is more visible. Photo: Zoe Blunt

The tree-sit blockade was a calculated risk. The four tree-sit platforms were suspended from ropes anchored to the treetops and to the bridge blockade. The ropes ran from the top of one tree, down to the bridge, through a pipe wedged under the pickup truck, out the other end of the pipe, and up to the top of the second tree.

Click on the diagram for a full-size image. A traverse line (not shown) connected the two trees like a high wire, allowing the tree-sitters to move from one tree to the other. Source: Elaho Valley Anarchist Horde: A Journal of Saquatchology.

The truck itself was filled with rocks, piled with logs and wrapped in barbed wire. Two signs warned that tampering with the structure would cause the platforms to drop, and the tree-sitters could fall to their deaths.

When the tree sits and bridge blockade were set up, the area was under a court injunction and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were keeping a close eye on the protest site.The tree-sitters were confident the RCMP would heed the signs and be very cautious when they moved in to make the arrests.

They were mistaken.

From July 26 to August 2, dozens of RCMP officers laid siege to the blockade. An Emergency Response Team was mobilized, and footage of rifle-toting sharpshooters storming over the bridge was broadcast on national television for a week. But as the days wore on, the cops grew visibly frustrated that they could not evict the protestors in the trees.

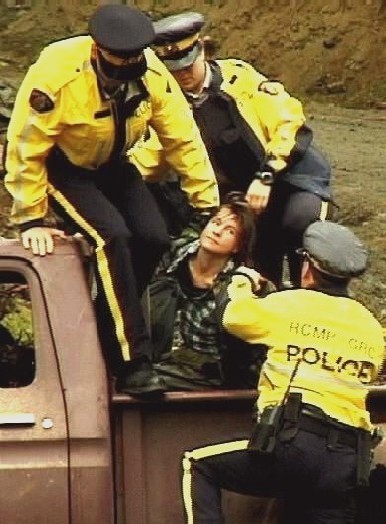

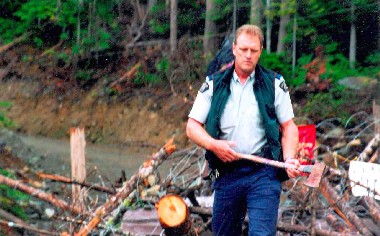

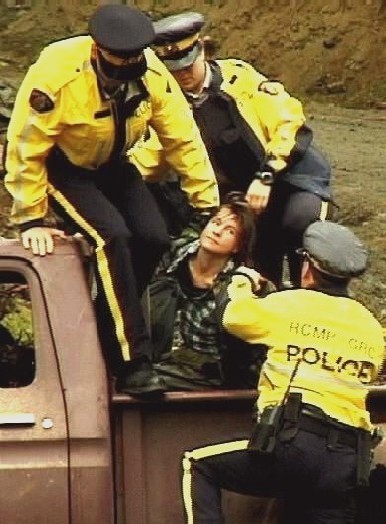

They took it out on anyone within reach. From his perch in the tree, Zarelli watched three officers drag me by the neck from the woods, twist my cuffed hands up behind my back, and throw me headfirst into a police trailer. I ended up with damage to my arms, shoulders and neck. (The cops told a judge later that I injured myself, and she took them at their word.)

Zoe gets busted. Photo: Daniel Gautreau

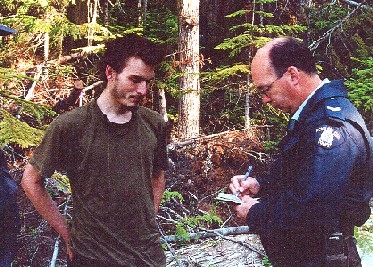

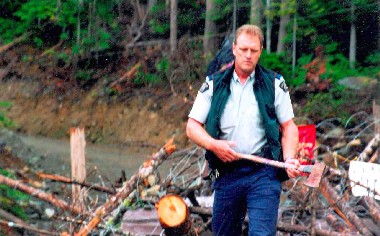

By July 28, officers had partially dismantled the blockade on the bridge. Then, without any warning, Insp. Bud Mercer used a pruning rod to cut the ropes supporting the platforms. What happened next became the focus of police investigations and court battles for six years.

RCMP Cpl. Darik Schaap dismantling the blockade. Photo: Zoe Blunt

When the lines were cut, the platforms suddenly tilted. The tree-sitters panicked when they realized the main support lines were no longer holding them. A witness reported:

The platforms drop, catching in lower parts of the canopy. One of the sitters is hanging from a branch screaming at the cops until helped back up. The action on the line is frantic, the goons with the big guns are off in the bush, police climbers start to climb the connected trees to cut off traverse points. The climbers move slowly, another cop on the ground yells instructions through a megaphone. (Journal of Sasquatchology)

Philippa Joly, another witness on the ground, watched in horror as the lines were cut.

“I remember seeing them cut the rope and then there was this slow-motion feeling – everything slowed down,” she recalls. “I saw the rope fall out of the tree. It came falling down. I saw other things falling from the tree. We were all holding our breath, waiting to see what would happen.”

The four young people remained in the treetops, clinging to the now-unstable platforms.

Metal rebar and a 55-gallon drum cut in half prevented police from climbing this tree. Photo: Zoe Blunt

Later, the police climbers assaulted the tree-sit in earnest. As the climbers started up the un-armored tree, the two sitters in that tree scooted across the high-wire traverse line and joined their companions in the armored tree. The climbers backed off and did not try to pursue the protestors.

“It was like living in a war zone,” Joly says. A police helicopter circled and hovered overhead. “[The police] were totally insane, with full-on camouflage and sniper rifles. Then they disappeared into the woods. And we’re like, what’s going on? Are our friends safe?”

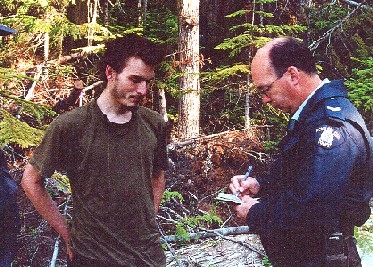

The standoff that followed lasted five more days before the four protestors climbed down and gave themselves up to be arrested. They later pleaded guilty and were sentenced to time served – one day.

Dennis Zarelli under arrest after nine days in the tree. Photo courtesy of Dennis Zarelli.

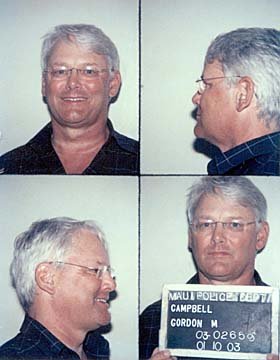

The shock of watching the officer cut the rope was too much for Zarelli to just let it go. In September 2000, Zarelli filed a complaint against Insp. Mercer, and a justice of the peace laid four criminal charges of aggravated assault against the RCMP officer.

It’s rare for police to face charges for acts they commit on the job, and Zarelli didn’t expect much to come out of it.

“I wanted to basically see attention drawn to the RCMP acting recklessly at the blockades,” he explains. “They were working with Interfor.” Officers stood by while a forest worker drove an excavator into the legs of a tripod that was occupied by a protestor, he says. The rest of us had witnessed similar incidents.

Protestors were hauled off and charged over minor acts of peaceful civil disobedience at the request of the company. But when loggers threatened us with guns and violence, we couldn’t even get the cops to take a report.

Two forest defenders were sentenced to a full year in the pokey just for standing in the road. Not one of the thugs who beat the campers and burned down the camp spent a day in jail.

Zarelli felt he had the potential to turn the tables and use the legal system to hold the police accountable, for once. But the charges against Insp. Mercer were stayed a month after they were filed. When the Crown prosecutor reviewed the police videotape, he said there was no evidence Zarelli’s life was in danger.

Then the harassment started: phone calls to Zarelli’s parents, his friends, and their employers from people identifying themselves as agents with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). His house was under surveillance for months.

Finally, the penny dropped. Word came that the RCMP had issued a warrant for his arrest – the Crown was charging him with obstructing justice for filing a false police report. (The perjury charge was added later.) Zarelli turned himself in.

The court drama that played out in December 2006 was surreal, Zarelli says. The Crown lawyer argued the protestors were trying to entrap the police. The blockade and the connected tree platforms were an “elaborate ruse,” according to Crown prosecutor Ralph Keefer. The claim that they were using civil disobedience to stop the logging was a charade, he said. The four forest defenders just wanted to get the cops in trouble on national television. The prosecutor accused Zarelli of planning the whole thing just so he could lay false charges against Insp. Mercer.

Incredibly, BC Supreme Court judge Sunni Stromberg-Stein agreed. In her reasons for judgement, she stated, “This was not an act of civil disobedience; this was a criminal act.”

Joly attended Zarelli’s trial because she wanted to witness the proceedings. “It felt really important to be at court because I was there when it happened.” She says the cops all told the same story, but on examination, their testimony actually underscored Zarelli’s complaint that they were negligent.

“All the cops said they couldn’t see how the ropes were set up,” Joly tells me. “All the cops gave statements affirming they couldn’t see the ropes from the ground, but the reaction when the ropes were cut led them to believe the setup was a ruse.”

“But the fact that they cut the ropes without knowing if it was safe to cut them just showed their negligence – which was Dennis’s original complaint.”

“The Crown was trying to show we hate the police,” Zarelli says. “He was bringing up stuff from ten years ago, things that happened in the Walbran [Valley] and Clayoquot Sound. I wasn’t even at those protests.”

Joly finds the Crown’s arguments unbelievable. “They were playing up this thing about us having a vendetta against Bud Mercer. Until that day he hadn’t even been there. We didn’t even know him.”

Zarelli was convicted of obstructing justice. He escaped a perjury conviction on a technicality, because the original complaint against Insp. Mercer was not taken under oath. Zarelli faces nine months in jail at his sentencing February 20, 2007.

Zarelli says the trial’s outcome is deeply disturbing, and not just for him.

“If people put their lives on the line to protect the environment, and the cops come in and take them out with reckless regards to their lives, the cops will now be able to refer to my case saying that environmentalists hate the cops and will lie in court for their cause,” he says bitterly.

The view from Lava Camp. Photo: Jeremy Williams, Wilderness Committee.

Today. the thousand-year-old firs and cedars still stand north of Lava Creek. Facing beatings and brutality, long prison sentences and death threats, the forest defenders held the line. We were forced out and hauled off in handcuffs, but we would not give up, and we kept coming back.

Interfor finally began serious negotiations with the Squamish Nation and a moratorium on logging in the Elaho Valley went into effect in 2001. The logging rights to the whole watershed now belong to the Squamish Nation, and the area north of Lava Creek is set aside as a Wild Spirit Place – to be protected in perpetuity.

Update: In February 2007, Dennis was sentenced to time served and probation – no jail time.