Mon, 04 Dec 2006

Kermode “Spirit” Bear

Groups say Big Greens brokered a bad deal, and now ramped-up logging is devouring coastal old-growth.

In February 2006, Greenpeace, Sierra Club and other groups celebrated a historic agreement with government and industry to bring an end to the “war in the woods” in the Great Bear Rainforest area of coastal British Columbia. Less than a year later, observers say the agreement may be unraveling. Timber companies have ratcheted up the rate of clearcut logging to unprecedented levels, and guidelines for sustainable logging are not being implemented.

Ian McAllister of Raincoast Conservation Society says the sudden increase in logging on the Central Coast is “unprecedented in fifteen years.”

“It’s unbelievable,” McAllister says. “It’s still just cut and run.”

“It’s talk and log,” says Qwatsinas (Ed Moody), hereditary chief of the Nuxalk Nation. “It is not a victory; everyone loses.”

What’s at stake is the largest intact coastal rainforest in North America – home to thousand-year-old red cedar forests, grizzlies, wolves, moose, mountain goats, black bears, and rare white spirit (Kermode) bears. Protected from logging and development by formidable mountains, this wild and rugged coastline stretches hundreds of miles from the tip of Vancouver Island to the Alaskan panhandle.

The ice-capped peaks rear up from the ocean, cut by fjords and salmon streams and covered with majestic cathedral forests. Whales and orcas swim through the channels and inlets, delighting tourists. First Nations communities fish, hunt, and gather berries, as they have done here for thousands of years.

The Great Bear Rainforest, we were told, is a wilderness legacy for our children and our children’s children.

How did this success story turn sour?

Twelve years of campaigning

It was members of the Nuxalk Nation who first invited non-native environmentalists to their traditional territory to witness large-scale clearcut logging in 1994. The following year, Greenpeace teamed up with the Nuxalk and other environmental groups to launch the campaign to save the place they named “the Great Bear Rainforest.”

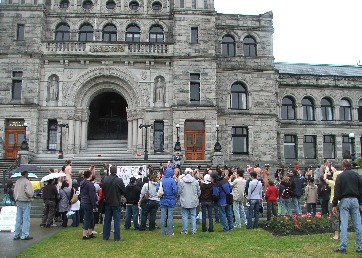

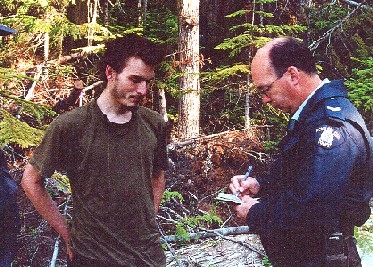

By 1997, Nuxalk members and their allies – Greenpeace, Forest Action Network, Bear Watch and People’s Action for Threatened Habitat – were blocking logging operations on Roderick Island, King Island and Ista, which is sacred to the Nuxalk as the place where the first woman came to earth.

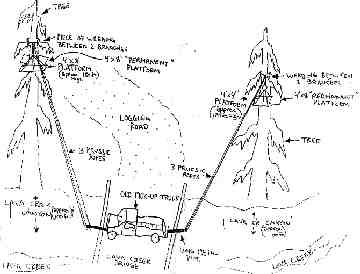

At dawn on June 6th, 1997, workers for International Forest Products (Interfor) arrived at Ista as usual to cut trees. Thirty protesters – including Nuxalk chiefs in full regalia – greeted the workers with a blockade and a huge tripod towering over the middle of the road. One protestor was locked down to a cement anchor buried in the road, while two more were perched at the apex of the tripod.

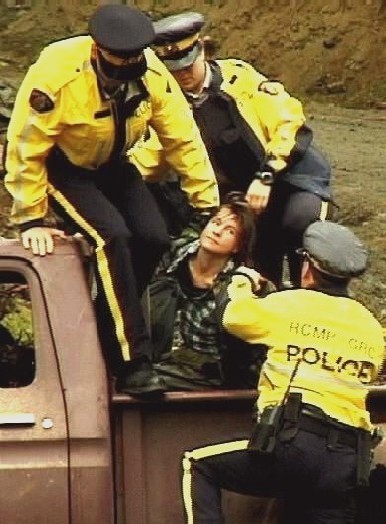

In total, fifty-five people took over the road and shut down Interfor’s logging operation for nineteen days. Twenty-four people, including six members of the Nuxalk Nation, were arrested when police arrived to enforce a court injunction. Qwatsinas was one of those arrested and convicted for blocking the road.

“I am charged with contempt of court,” Qwatsinas – a large, handsome man in his prime – told Justice Vickers at his sentencing in 1999. “Yet there is continuous contempt of our culture, our heritage, our lands and our rights. Logging companies coming to our land without our consent show contempt of our laws, our land, our people.”

Indigenous people in Canada are known as First Nations, and unlike their counterparts in the U.S., most First Nations in British Columbia retain legal rights on their traditional land for hunting, fishing, gathering medicine, and decision-making about resources. Recent high court decisions uphold these rights. But court challenges can take years, and when faced with the imminent threat of “illegal” logging or development on their traditional territory, many First Nations in B.C. have resorted to acts of civil disobedience like blocking logging roads.

In the 1990’s, massive industrial clearcutting was already taking place – without the permission of First Nations – under the auspices of the province, which also hosted a process called the Central Coast Land and Resource Management Plan (CCLRMP). The process was widely condemned as a “talk and log” exercise, until Sierra Club and Greenpeace set their sights on the planning committee. The groups won a moratorium in 1998 to suspend logging in intact rainforest valleys in the Central Coast while they participated in the CCLRMP process.

Meanwhile, environmentalists organized an international markets campaign to lobby buyers of B.C. wood products around the world. As the boycott campaign picked up steam, companies like Home Depot and Ikea dropped their B.C. wood contracts, and the pressure was on to find a compromise.

“Customers don’t want to buy their two-by-fours or their pulp with a protester attached to it. If we don’t end it, they will buy their products elsewhere,” Bill Dumont, chief forester at Western Forest Products, told the Vancouver Sun in May 2000.

Also in 2000, Greenpeace, ForestEthics, Rainforest Action Network, and Sierra Club of Canada – known collectively as the Rainforest Solutions Project (RSP) – made a decision that changed the course of the campaign. According to Qwatsinas and others close to the Great Bear Rainforest, it was a serious strategic error.

While negotiating the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement, the RSP formally agreed to end their protests, blockades and markets campaigns. For the duration of the agreement, there would be no more high-profile blockades of logging operations on the B.C. coast, no lobbying international wood buyers, and no hardball criticism of the process to the media.

But did the environmentalists give up their only bargaining chip?

“They made the Central Coast an environmental-protest-free zone,” Qwatsinas says. “We can’t go out and blockade or protest. We’re neutralized, really. They [participating groups] are handcuffed. How are you going to set forth your demands at the table when your will is broken?”

The Big Greens kept their promise to keep the peace with good faith and due diligence. It remains to be seen whether the timber industry and the provincial government will do the same.

As a hereditary chief with a sworn duty to protect the land, Qwatsinas has been on the front lines of this battle for more than fifteen years. Now, watching clearcuts chewing up habitat for salmon and bears, he can’t understand the enviro groups’ concessions. “They’ve given away too much. It takes time to get the market campaign, the boycott campaign going again. Think about those strengths that were given up – the power that they had in making demands, but it’s gone now. What else can they use?”

Victory through Compromise

RSP forged ahead with negotiations about how much land to protect and how to log the rest. With the Joint Solutions Project, the eco-groups collaborated with industry, government, labor groups and First Nations to establish interim agreements, logging moratoriums and other small victories.

Since the parties had pledged to base the outcome on the best independent science available, the province requisitioned a scientific review of the Central and North Coast flora and fauna to make recommendations about habitat protection. Seventeen scientists comprised the Coast Information Team, and their findings in 2005 stated that setting aside a minimum of 44 to 50 percent of the land area would be necessary to save ecosystems and wildlife.

In 2006, the final agreement was announced with fanfare by a provincial government eager to paint itself green after years of cutting parks budgets and opening wilderness areas to development and logging. But the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement only commits to a “conservancy” designation for 32 percent of the land, part of which is open for mining, and all of which may be open to roads, hydroelectric projects, tourism, and other uses.

Sierra Club campaigner Lisa Matthaus admits the amount of protection was inadequate. “The protected areas alone are not sufficient, but this is a political compromise. You need to have a lot of parties in agreement.”

“We wanted to meet the recommendations of the scientists [on the Coast Information Team],” she told The Martlet in 2005, “but we couldn’t.”

The quantity and quality of the protected areas greatly concern conservationists in the region. They cite the lack of connections and wildlife corridors between small, widely scattered conservancies. Worse, wolves, a key predator, were simply left out of the habitat surveys.

McAllister estimates that eighty percent of salmon streams are outside the protected areas, along with seventy percent of grizzly bear habitat. He notes that even inside the conservancies, trophy hunting will be permitted

In May 2006, the B.C. Legislature officially designated 24 conservancies in the Great Bear Rainforest. As of December 2006, 61 more were still awaiting legal recognition.

Although they recognized that the agreement didn’t meet minimum standards, environmental groups hoped more habitat might be saved through special forestry practices known as ecosystem-based management (EBM).

Boom and Bust

If one-third of the land base of the Great Bear Rainforest is protected, according to the deal, then two-thirds will be logged. How it will be logged is still the subject of debate.

The logging industry, environmental organizations, communities, labor unions, First Nations and the B.C. government agreed to phase in new EBM logging practices by 2009. The Rainforest Solutions Project website describes “lighter touch practices” that would “protect old growth, wildlife habitat, sensitive watersheds and salmon streams.”

Instead of starting to adopt these gentler practices, it appears some – if not most – timber companies are stripping the land as fast as possible before the 2009 deadline.

Ian McAllister sums up the current logging practices: “Clearcutting. Everywhere on coast it’s the status quo, clearcutting. It’s no different than what you’d see thirty years ago. In some places they may be doing something different, but the vast majority is status quo logging.”

Raincoast Conservation Society has conducted research and education about the Great Bear Rainforest since 1990. “I’ve just returned from a month of exploration on the coast, looking at recent logging practices. Based on what I’ve seen, I’m not hopeful. They’ve had years – decades really – to get their act together and agree to basic principles of forestry. They’re still not adhering to those principles,” McAllister said.

“They’ve been told that will change in 2009, so they’re just trying to log as fast as they can, and get roads into as many valleys as they can. There’s no interest in community employment or long term sustainable logging jobs.”

The clearcuts are bad enough, but some timber companies are leveling the rainforest and then hauling out only the best trees, mostly red cedar, leaving the rest to be burned as slash or rot on the ground. High-grading wastes millions of tons of wood each year, and it’s universally deplored as wasteful and contrary to sustainable forestry. The combination of clearcuts and high-grading resembles the world’s worst slash-and-burn logging.

“It’s a huge concern,” McAllister says, “because this is the forest species with the greatest economic value, and it’s the rarest species in the temperate rainforest. And it’s being logged at an unsustainable rate.”

“In our October surveys of recent logging operations on the Central and North Coast, all of the cutblocks had hemlock and spruce stacked high ready for burning,” McAllister relates.

The final insult for coastal communities – and loggers – is the destination of much of this high-grade timber: foreign mills.

The Truck Loggers Association (TLA) tackles the problem head-on in a position paper delivered to the province November 22, 2006.

“Today, log shortages are common across the coast,” the paper states. “At the same time, increasing volumes of exports continue to leave the province, while many independent mill-investors are struggling to secure wood in the marketplace to sustain their operations.”

Qwatsinas compares the current logging boom to the one in Nisga’a territory just before a treaty agreement was signed. “They accelerated logging up to five times the rate they were cutting before. Obviously, they’ve accelerated the logging in the Central and North Coast too.”

Even the RSP groups are getting concerned. A press release in September 2006 charges the government has missed deadlines it agreed to in February 2006, including a pledge to legislate EBM measures and fund a scientific oversight group. Also, they note, “some forest companies” still have not begun the eco-logging practices they promised three years ago.

Merran Smith of ForestEthics says: “We stood on the stage and announced to the world a new conservation approach for the Great Bear Rainforest, These agreements are now at risk because a cornerstone of the agreement, ecosystem-based management, is faltering. We are tired of big talk with no action.”

Pat Bell, a B.C. government minister, responded to the RSP’s complaints last month in an interview with the Ottawa Citizen, saying the oversight group would be established within weeks, and the initial objectives for ecosystem-based management would soon be available to the public. But Bell was vague about the time frame for “phasing in” EBM.

“There could be components of it in legislation next year,” he said, “but the commitment that I think is really important was full implementation by 2009.”

Those watching the clearcutting on the North and Central Coast are not likely to be comforted by assurances that things may change in a few years.

Division in the ranks

Qwatsinas calls the Great Bear agreement an “empty box.” Essentially, the deal is a framework, with timelines set for the parties to fill in the details later. Ecosystem-based management itself is left undefined. Even when a set of practices is eventually spelled out, the definition will be subject to change.

The David Suzuki Foundation, one of Canada’s largest and most respected enviro groups, wouldn’t endorse the Great Bear agreement for this reason. “There’s no guarantees that acceptable EBM practices will be adopted,” Bill Wareham said. “The agreement does not meet our expectation.”

Several other groups dedicated to the Great Bear Rainforest have walked away from the table, including the Forest Action Network, Spirit Bear Youth Coalition, Valhalla Wilderness Society, and Raincoast Conservation Society.

Valhalla Wilderness Society has been collecting scientific data and working to protect the coast for eighteen years. In a 2004 memo, society chair Anne Sherrod blasted the RSP:

In the future, while logging the unprotected ecosystems, timber corporations on the mid-coast will enjoy the signed agreement of two of B.C.‘s largest groups, Greenpeace and the Sierra Club, as well as the U.S.-based ForestEthics and Rainforest Action Network. The groups that will continue working on additional protection on the coast – such as VWS, Raincoast, Forest Action Network and David Suzuki Foundation – will be blocked by the B.C. government and timber industry, using the agreement signed by the RSP groups as a “done deal.”

In the last few years, some environmental groups and activists have lost patience with this. After 15 years of seeing this happen, there should have been more learning, more awakeness to the crisis of what we are losing and how we are losing it. Instead we have the rhetoric and delusion of “win – win” agreements.

First Nations people are also divided in their response to the agreement. Even within the Nuxalk Nation, the band council supports the process, while traditionalists like Qwatsinas and the House of Smayusta oppose it vehemently.

The dissent is further fueled by the fact that the agreement failed to respect a protocol with the Nuxalk members who first invited Greenpeace to their territory in 1994. The protocol between Greenpeace and the House of Smayusta stated no deals would be made without the approval of the First Nations partners.

“It was a bold move for Greenpeace Canada to ignore the protocol and make the [Great Bear] agreement without our approval,” Qwatsinas notes. “The sovereignty of Nuxalk lands and rights in our sense took a back seat.”

Elsewhere on the coast, the Kitasoo Nation has signed the deal and now hopes to reap the benefits – by logging Green Inlet, part of its traditional territory. Although almost half of Kitasoo land is protected, and Kitasoo Forest Products is cutting trees selectively instead of clearcutting, the project has brought the wrath of Simon Jackson, founder of the Spirit Bear Youth Coalition. Jackson says opening a key area to logging could threaten the future of spirit bears.

“Everybody thought the white bears were protected with that announcement,” he said. “A lot of great steps were taken . . . but it didn’t protect the spirit bear.”

Simon says the Green watershed is needed as a genetic buffer zone.

“What’s happening now is that if logging occurs in the Green, bears will be displaced from their homes and the likely forced migration route they’ll take is over to Princess Royal Island, where they’ll dilute the gene pool and render the area thus far protected useless.”

Grant Scott, a Kitasoo representative, disputed Jackson’s facts, pointing out the area being logged is not prime black or spirit bear habitat.

“We talked to him about this. We said, ‘Simon, this isn’t spirit bear country,’ but he apparently doesn’t agree,” Scott says.

B.C. lands minister Pat Bell says that logging in spirit bear habitat is no problem, as long as “the operation is in keeping with the February agreement, which protected key spirit bear habitat, while leaving other areas open to ecosystem-based logging.”

The coalition says the agreement has protected only two-thirds of the spirit bear’s crucial habitat and that the province is back-pedaling on its commitment to protect the rest.

Now that logging has begun in the last third, the small spirit bear population – estimated at about 200 animals – faces an uncertain future, said executive director Salimah Ebrahim.

Action and collaboration

The announcement of the final agreement set B.C.’s environmental community abuzz with debate over tactics and strategies in the Great Bear Rainforest. Clearly, Greenpeace has switched its focus from confrontation to cooperation, no doubt to stay in line with the changing priorities of a protest-weary public. Similarly, “finding solutions” and “building consensus” have become the catch phrases of foundations funding the large eco-groups in the U.S.

The evolution of Greenpeace from a rag-tag band of protestors to a multinational bureaucracy may explain its newfound commitment to collaboration with industry and government. Ingmar Lee, a journalist and old-growth forest activist from Vancouver Island, says the group has adopted the corporate model it once deplored.

“This is exactly what happens to forest protection activists who graduate from the frontlines into paid positions and begin working themselves up the ladder,” Lee says. “Once they’re into the $60,000-a-year bracket, they just quite simply cannot relate to anyone in the movement, but they can sure hobnob with the corporate logging executives. They begin to see how the ‘real world’ works, and they begin to understand that if they cooperate, they will start to get some of that power.”

By seeking closer relationships to government and industry, Sherrod says, environmental organizations can become alienated from their actual power bases: solidarity with other environmental groups, widespread public support; and the reality of what is happening in our environment as documented by science. “I really don’t think it’s a problem particular to big environmental groups or rich ones,” she says. “I’ve known lots of little ones to do this. And some large groups play positive roles in the movement.”

The Valhalla Wilderness Society has campaigned tirelessly for the Great Bear Rainforest, but it never participated in the negotiations. “We think decisions on public lands should be made by open public process, and certainly in conjunction with First Nations and in full accord with their rights,” Sherrod says. The Society did work with the planning table, contributing its scientific surveys of potential protected areas, for example, but eventually there was a split between the environmental groups.

“I think the real problem is that negotiations with industry bring about a fundamental incompatibility in working methods,” Sherrod continues. “How can colleague environmental groups have solidarity when some of them are having meetings with the logging companies behind the backs of the others, making decisions that will affect everyone, and keeping them secret until there’s nothing that can be done about it?”

Dani Rubin, secretary of B.C. Pathways, says the exclusionary process inflicted “collateral damage” on the entire B.C. environmental movement. “I remember Don McMillan of Interfor telling me that the industry had a plan for us [environmentalists],” he says. “It’s pretty clear now that the corporate strategy was to divide the environmental movement by electing to negotiate only with the ‘pragmatists,’ leaving the rest of us out in the cold.”

Rubin says in the rush to get to the table and make a deal with industry and government, Greenpeace, ForestEthics, and Sierra Club swept aside pre-existing agreements with several environmental groups. Not only that, but an “umbrella of silence” has stifled open discussion about the deal and how it’s being implemented.

Many observers report that one of the conditions imposed on those who joined in negotiations was a ban on any public complaints or criticisms aimed at the process or any of the participants. Of course, the parties involved are not disclosing details about any such restrictions.

Qwatsinas suggests more groups should be speaking out about the agreement’s shortcomings, but “I don’t think they can. Some of their hands are tied and the gag order is in place.”

Besides the forest, the wildlife, fresh air and clean water, a substantial financial package is at stake for the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement participants. $120 million has been raised or pledged by foundations and the government, and it’s earmarked for First Nations sustainable economic development and conservation projects. (Not to mention the cost of the planning process itself.) And the Big Greens’ high-profile campaign, with the spirit bear as its mascot, has served them well by raising their public relations profiles and expanding their donor bases.

Lee says a cost-benefit analysis of the money spent on the Great Bear Agreement comes up short. “We’ve found organized, institutional environmentalism [in B.C.] has failed over the last four years to accomplish anything,” he complains. “The successes have come from individual grassroots efforts that have basically bypassed the entrenched, bureaucratic, environmental institutions that have been sucking up the enviro-buck and just not getting the kind of accomplishments we need.”

Lee is not surprised that the RSP groups are getting “stabbed in the back” by government and industry apparently reneging on the spirit of the agreement.

“I just believe that we should be working together against these incorrigible forces of destruction rather than working together with them,” he says. “I have always advocated a broad spectrum of environmentalist effort, but the grassroots activist community has been excluded from the project from the start.”

Lee understands the need for no-compromise action; as a key member of the campaign to save Cathedral Grove from a misguided parking lot, he spent over two years helping to coordinate a campaign of road-blocking and tree-sitting that ultimately forced the province to back off.

Qwatsinas also makes a distinction between the efforts of grassroots groups versus the Big Greens. “I’m glad there are some out there, groups like Raincoast, trying to make an honest effort, protecting the environment, who are not handcuffed by the process.”